Farm Life

A Day in the Life of An Oyster Farmer

Oyster farming was initially started on the East Coast at the Chesapeake Bay in 1601, and migrated West as the pioneers reached the Pacific Ocean. Early methods of oystering exclusively harvested natural oyster reefs using a Hand Tong, a device that had two rakes juxtaposed to one another and opened and closed like a mouth, with the tines acting as teeth.

St. Mary’s River Watershed Association, Inc. http://www.rereefthebay.org/gallery_monitoring.html

This method remained largely inefficient until 1854 when farmers discovered power dredging (Image 2). This technique involved dragging a rake with a wire basket attached, along the oyster reefs, “scraping” the oysters off the ocean floor.

This method was wildly popular due to its efficiency and ease of use. However, the damage caused by power dredging to the oyster reefs was more significant than the farmers realized and oyster populations plummeted to record lows. Current native oyster populations are less than 1% of historical population numbers. Modern oyster farmers now treat oysters more like agricultural crops than just a natural resource; focusing on conservation and environmentally friendly harvesting methods. The oyster farming process is a simple, yet delicate process.

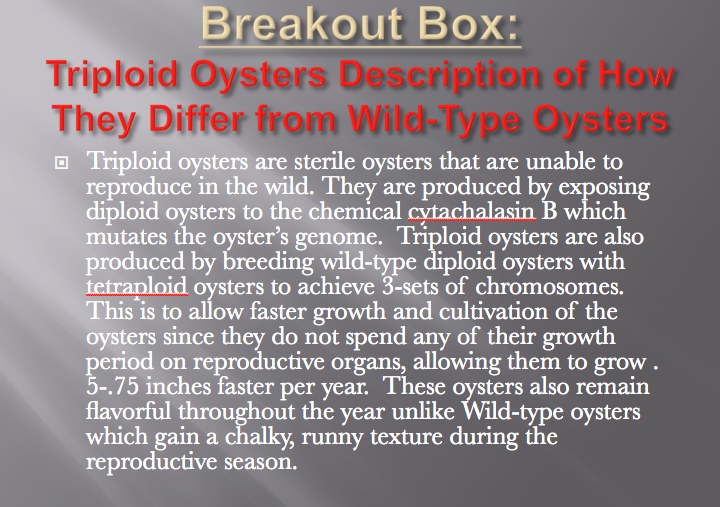

Oyster farmers first collect natural “spat” (oyster larvae) collected by placing bags of clean oyster shells (cultch material) in the water during forecasted settlement of planktonic oyster larvae, typically in late spring (for Ostrea and olympia oysters) after males have released their sperm and females have incubated their brood for approximately 10 days. Females typically release their larvae (spat) once the high-tide water temperature is around 55 degrees Fahrenheit. For other oyster species such as the Crassostrea oysters, it is much the same process except their breeding season takes place in mid-summer when high tide temperatures reach approximately 70 degrees Fahrenheit. The cultch is then left in the water for several weeks and then removed to a nursery area. This technique is not the most effective technique in that over 50 spat can attach to a single oyster shell and as they grow, they compete for space and kill each other off. In order to decrease the amount of time to gather and increase the survivability of the oyster spat, oyster farmers have created oyster hatcheries to streamline the process. Hatcheries attach spat to oyster shells in a very regulated process. Oyster shells are ground up into microfilaments and are then added to tanks containing oyster spat and left for a week to two weeks. The oyster shell particulate is so small that only one oyster larvae is able to attach to a single oyster shell, ensuring all the spat has its own space in which to grow. This process is extremely expensive due to the necessity of settling tanks, heaters, and machines to produce phytoplankton slurry to feed the oyster larvae. Almost all of the oyster spat produced by hatcheries are triploid oysters.

Oyster farmers typically use a nursery to prepare the oyster cultch for cultivation in the open bay. The oyster cultch is especially vulnerable to external variables and predators and as such, are typically housed in mesh bags suspended from rafts or long lines in shallow (+0 to -3 ft) or middle (-3 to -5 ft) intertidal ranges to allow the oyster cultch to ‘harden’. Hardening is the process of the oyster shell thickening to adapt to the intertidal climate. If a beach is well protected against predators and has a stable (non-muddy) foundation, cultch bags can be placed directly on the beach’s intertidal region underneath a predator net for growth. As the oyster cultch grows over several months, they are periodically moved to larger mesh bags in order to allow continued room to grow.

Once the cultch oysters have grown to be over ½”, they are subjected to a number of different growth techniques, much like a farmer’s choice to grow crops outside or in greenhouses. Oyster farmers use different techniques from two main methods, On- or Off-Bottom Culture Methods.

Bottom-Culture

Historically, oyster farmers across Puget Bay have grown oysters using varying forms of the Cultch and Cluster Method. This varies from leaving the oyster cultch in large mesh bags placed along the beach of the tideland and covered in predator nets to using the Stake Culture Method. The Stake Culture Method is used in tideland that has a muddy consistency by placing stakes 36” into the substrate, spaced approximately 2 feet apart to allow farmers to move between the stakes.

Small cultch’s of oyster seed are hung on a thin polypropylene or metal wire and hung or wrapped around the stake to hold the oysters in place during growth. Maintenance by farmers is needed to ensure even spacing of the oysters during growth and to limit predator damage to the crop. Maintenance occurs during the low tide while the stakes are exposed on the beach.

Another technique commonly used by oyster farmers is the Rack and Bag Culture Method. This technique is essentially the same as the Cultch and Cluster Method, but is used on beaches with a muddy substrate. Rebar racks are placed on the beach to elevate the cultch bags above the substrate. Each rack can accommodate 4 large grow bags, which are attached to the racks using cable ties or rubber straps.

Over a period of a few months, each bag is rotated on a biweekly basis on the rack to ensure even growth of the oysters and to ensure no fouling (algal growth) occurs. Approximately 200 oysters are able to fit inside each grow bag.

Off-Bottom Culture

A different approach to shellfish aquaculture is to grow oysters detached from the ocean bottom. This is done through a number of methods; a commonly used one is to use the Floating Culture Method. Oysters are placed on grow-out trays or cages, which are then hung or stacked on sink floats.

This method allows oysters to be grown in high densities since water circulation is higher, making food resources more available and limiting predation. This method is highly maintenance intensive and requires weekly monitoring to limit oyster clumping and metabolite buildup. Another variation to the Floating Culture Method is the Longline Culture Method, is similar to the Floating Culture Method in that long polypropylene ropes are secured to an anchor at the ocean bottom and secured to a float on the other end of the strand to suspend the oysters. These strands of oyster cultches can also be hung from many different positions, but they are typically spaced along the polypropylene rope every six to eight inches and threaded by drilling a hole through the shell.

Each longline is spaced approximately eight feet apart from one another for optimal growth and ease of maintenance by the farmers.

The problems with Off-Bottom Culture methods are that these methods are typically more susceptible to environmental factors such as storm damage and seaweed fouling. These methods do, however, allow the use of beaches unsuitable for natural oyster growth and significantly reduce marine life predation.

Leave a Reply